Jimmy Graham, Elite Wide Receiver Talent and Predictability

After a somewhat controversial piece on Graham, I’ve decided to look at a different angle that may help define Jimmy Graham’s true fantasy value in 2013: Would his value change if he played wide receiver?

The Need for Elite Receivers

I’ll introduce this section with a piece from The Late Round Quarterback: 2013 Edition:

One thing that’s incredibly noteworthy about this chart is the number of receivers who had multiple top performances. I’ll stress it throughout this literature, but having a receiver who’s consistent from week to week is one of the most underrated advantages in fantasy football. Clearly it’s difficult for receivers to consistently rank as top performers, as only seven of them – just one more than quarterbacks (remember, you’re starting double the amount of receivers as quarterbacks) – did it six or more times. And only four of them did it seven or more times. If you had one of those receivers (Calvin Johnson, Brandon Marshall, Demaryius Thomas and Vincent Jackson), you created a significant advantage over other teams in your league. This is one of the main reasons that, although Value Based Drafting may tell you otherwise, drafting a stud receiver is worthwhile.

By “top performers”, as noted in the book, I’m referring to players who finish in the top 12 at their position during a given week. In other words, I’m looking at WR1’s in 12-team leagues.

Essentially, if we were to use the term “elite” to describe the top of any fantasy football position, we may want to consider coining it for wide receivers. The difficulty for wide receivers – compared to running backs and quarterbacks, at least – to post top numbers each week in fantasy football is unmatched when you factor in ADP, supply and demand and position predictability drop-offs. This type of analysis isn’t necessarily captured with VBD analysis though, as weekly numbers are simply added up to form the projections that are used.

I’ve heard the argument, “Jimmy Graham puts up wide receiver numbers and he’s a tight end, therefore I need Jimmy Graham on my team.” And while the statement is correct (in terms of his 2011 numbers), we must recognize that Jimmy Graham isn’t a wide receiver. That makes a huge difference.

Let me put it this way: If Jimmy Graham were to score similarly to how he did in 2011, there’s a chance I’d value him higher if he could be slotted as a wide receiver, even with identical production at tight end.

This will sound nuts to many, and I’m sure I’m about to lose a few readers, but bear with me.

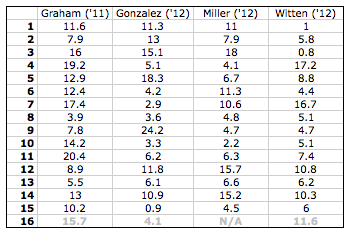

Let’s bring back the chart that I used in my last aritcle on Graham:

Graham’s production was consistent as can be in 2011. Were there unbelievable games if we were to consider this output at wide receiver? Not really. But his cumulative numbers would’ve placed him as a top-5 wide receiver. When you consider the lack of monster games, that’s borderline incredible. It’s also desirable. I want that in a wide receiver because the wide receiver position is, as I like to say, an inherently inconsistent one.

Graham’s production was consistent as can be in 2011. Were there unbelievable games if we were to consider this output at wide receiver? Not really. But his cumulative numbers would’ve placed him as a top-5 wide receiver. When you consider the lack of monster games, that’s borderline incredible. It’s also desirable. I want that in a wide receiver because the wide receiver position is, as I like to say, an inherently inconsistent one.

Tight end play, however, is just as unreliable. In fact, if you look at my 2012 study on predictability using the coefficient of variation, you’d see that, of the main four fantasy positions, starting tight ends are the least predictable from one week to the next.

If you recall, I talked in my last Graham piece about how and why VBD isn’t a linear equation. We should never assume a drop off from one player at a position to the next is constant. We have to be cognizant where significant drop-offs occur. With Value Based Drafting, the fantasy masses see Jimmy Graham as so much better than the rest of his position, showing a less linear (consistent) decrease in point output from one tight end to the next. It’s a very correct conclusion.

But interestingly enough, the same type of logic can be attributed to the coefficient of variation, a measure of predictability to one’s average.

The Coefficient of Variation

Fantasy football is a weekly game, and we base our Sunday decisions on a seven-day calendar, not a season-long one. I’m not setting my lineup in September and never touching it (aside from best ball leagues). Instead, I’m setting my lineup on Saturday night or Sunday morning, hoping to maximize the output of my team for that given week.

If you reference the coefficient of variation chart again, you’d see that there’s a clear drop-off after the WR11-WR20 (WR2) group. After these wide receivers – and heck, this next group would still include starters in most leagues – predictability becomes iffy. This idea drives the demand for early-round wide receiver picks. Although the end-of-season numbers may appear similar or low in volatility, knowing you have a plug-and-play wide receiver matters, especially when you have deep lineups. To be fair, most lineups at wide receiver are deep, as a majority of leagues start at least three in a given lineup each week. Compare that to tight ends, where a standard lineup starts just one.

Peep the tight end position and take a look at the coefficient’s drop. It’s not as large, mostly because the top tight ends weren’t as reliable as top wide receivers in 2012. And while Graham is just kind of lumped into that top-5 tight end category, it still shows that the guys at the top of the position aren’t as predictable, and in some ways, meaningful, to the rest of their position like wide receivers are. Considering Graham has given us one year of data where he was as consistent as he was, it’s a little frightening to think about the true unpredictability for any tight end.

For the record, the wide receiver dip continues when you look at WR31-40. The coefficient of variation drops to .89, a number comparable to TE11-TE15. It’s not all that surprising, as tight ends are less predictable to their average because they see fewer snaps and fewer targets each week. Every once in a while they have a multi-touchdown game, and things get thrown off.

It may seem that this favors Jimmy Graham, especially at tight end. After all, if you draft him, you’re now throwing away the risk of starting a mediocre player at the most unpredictable in fantasy football. Again, you have to ask: At what cost?

Supply and Demand and Average Draft Position

As I mentioned in the first Graham piece, there’s a potential aspect of Value Based Drafting that’s often overlooked: Average Draft Position. Though FootballGuys.com recently revisited their famous Value Based Drafting strategy and included notes on ADP, the majority of fantasy owners haven’t caught on. That’s why, in my May book release of The Late Round Quarterback: 2013 Edition, I stressed the idea of Market Value Drafting.

Essentially, Market Value Drafting takes VBD principles and apply average draft position data to them. Why is this important? Well, VBD is based on personal projections. If you’ve projected a player to put up Pro Bowl numbers, but everyone else in your league (and the world) thinks he’s only worthy of a 13th round draft pick, why would you draft him in Round 6? You wouldn’t. Instead, you’d try your hardest to conform to his ADP in order to maximize the draft value of that player. Keep this in mind.

Pretend that we’re starting two wide receivers, two running backs and one tight end in our 12-team league lineup. Traditionally, the 24th wide receiver – the last starter selected at draft time in this league – will leave the board around the end of the fifth or beginning of the sixth round. And the 24th running back – again, the final starter drafted in the league – will leave the board in the middle of the fifth round.

The 12th tight end? He doesn’t leave the board until the end of Round 11.

Please, lean back in your chair for just one second and think about what this means. If we were to assume a constant drop-off in projections from one tight end to the next (I know this isn’t the case, but continue to assume), the tight end variance (Jimmy Graham to the last tight end selected) is spreading across 10 rounds. At receiver and running back, the spread is cut in half.

Remember, there’s a significant predictability decrease from the top 20 receivers to the next group. When you get past Round 5 or 6, the place where the final starter at wide receiver is selected, you enter a more ambiguous area. Of course we’re assuming each wide receiver finishes where he’s drafted, but isn’t it fair to think that the probability of a top 20 ADP receiver finishing in the top 20 is greater than, say, a receiver with an ADP ranked between 31 to 40? (If you want more information on this, I have a chapter on yearlong predictability in The Late Round Quarterback: 2013 Edition.)

The drop-off we all speak to is not just in terms of points scored. It’s also in terms of how predictable a position is, which is important because fantasy football is a weekly game. In addition, the drop-off compared to average draft position is just as vital. Keep in mind, this isn’t to say Jimmy Graham isn’t predictable, because he is. It’s more to say that elite wide receiver predictability may be more important than elite tight end predictability.

Jimmy Graham as a Wide Receiver Could Mean More to Fantasy Football

We could classify Graham’s attractiveness as a wide receiver in fantasy football like the following:

1. Because of ADP and supply and demand, top wide receivers are arguably needed more in fantasy football than top tight ends.

2. Because of predictability drop-offs, elite wide receiver play is arguably more important than elite tight end play in fantasy football.

3. If we assume Jimmy Graham produces as he did in 2011, he would not only be a top 5 wide receiver (a second round draft choice), but he would arguably the most consistent wide receiver outside of Calvin Johnson.

It sounds absurd. It sounds wrong. But if Jimmy Graham were able to play wide receiver in your fantasy football lineup, and if you were 100 percent confident that he would produce as he did in 2011, there’s an argument to be made that he’d be more valuable than if he had the same production at tight end.

This All Comes Down to Confidence

This piece isn’t to say that Jimmy Graham’s value significantly changes if he were to be slotted at wide receiver. Instead, it’s to show that drafting without looking at the entire picture could cause a less valuable team. Part of the reason I’m skipping on Graham in Round 2 is because that area of the draft consists of the desirable wide receivers I speak to above. Brandon Marshall, AJ Green and Dez Bryant, due to the position they play, are more important to my fantasy football strategy.

Look, I know I’ve exhausted the angles at which you can really argue for or against Graham. Do I understand his allure in being selected in the second round of redrafts? Of course. As I’ve said many times through The Twitter, Graham’s ceiling is high and the attractiveness to have a player who appears to be so much better than his peers is nearly unmatched.

The idea of drafting Graham early comes down to confidence. Are you better and more willing to plug-and-play a late-round wide receiver or a late-round tight end? Do you believe in Jimmy Graham’s ability to post nearly 200 standard fantasy points again? Are you confident that the running back pool is deep enough that you can afford to not select one in Round 2?

You have to continue to question what is simply accepted. Without that, we’d all have the same fantasy football teams.